Caribou: Mountain and Woodland

Caribou in the Sahtu

If one thing could be singled out that binds the people of the Sahtu most strongly to their land and heritage, it would be caribou. This animal has always been a staple of Dene subsistence, and its seasonal migrations have determined people's movements on the land.

There are two sub-species of caribou in the Sahtu - barrenground, Rangifer tarandus granti and woodland, Rangifer tarandus caribou. Within the woodland caribou, there are two ecotypes - the mountain and the boreal. Most people in the Sahtu, however, know their local caribou by their herd names such as Bluenose East, Bluenose West and Cape Bathurst (in the barrenland).

Barrenground Caribou

Barrenground caribou have long legs ending in large, broad, sharp-edged hooves, which give good support and traction when traveling over snow, ice or muskeg. In winter, the pads between the hooves shrink, and the hair between the toes forms tufts that cover the pads, so the animal walks on the horny rims of its hooves and the hair protects the fleshy pads from contact with the frozen ground.

The colour of a caribou's coat varies seasonally. The old fur that has faded to very light beige over the long winter falls out in large patches revealing a new chocolate brown coat. When the moult is complete, caribou are uniformly dark brown with a white belly and white mane. Adult males also sport a white flank stripe and white socks above their hooves. In the fall, as white-tipped guard hairs grow out through the summer hair, caribou become a more uniform light brown. The exceptional warmth of the winter coat is the result of individual hairs which are hollow. The air cells in the hair act as an insulating layer.

Barrenground caribou have the largest antlers in relation to their body size of any deer species and are the only species in which females grow antlers. Antlers are shed and regrown each year. Calves have short spikes, but as an animal gets older, antlers increase in size and complexity. Adult males have the largest antlers and they may be shed as early as November, just after the rut. Younger males may retain their antlers until the following April, while females lose their antlers after calving in June.

Behaviour

Caribou are generally silent animals except after calving and during the rut. After calving, cows communicate with their young in short grunts. Males vocalize during the rut with a snorting, bellowing sound.

Another sound which caribou make, though not vocal, is the sharp clicking noise resulting from the movement of the tendons and bones just above the hooves. This noise is heard most clearly on calm cold days as large groups of animals journey across the tundra.

When migrating, they walk at about 7 km/hr, covering between 20 and 65 km a day. When startled, a caribou runs in a loose, even trot. The head is held high with the nose up and the tail erect. When galloping at top speed most caribou can outrun wolves, their major predator, but wolves close in quickly on any animal that stumbles or takes a wrong turn.

Caribou are excellent swimmers. Their hollow hairs enable them to float high in the water and their broad hooves propel them along at speeds of about 3 km/hr.

top- caribou calf

above - caribou trail

The difference between caribou hide and moose hide is that caribou hide tends to get dried up easily when smoking so it is seldom tanned …

Some women were telling me that to tan a white caribou hide, it is a lot of hassle trying to work on it. And at the same time, you have to keep it real clean so it won't get dirty.

You work on the hide like you would a moose hide, but you don't tan it. The white caribou hide is used for making white slippers or gloves.

From oral narratives by Pauline Lecou, Fort Good Hope

From the Committee for Original People's Entitlement collection.

Bull caribou

Some writers believe the word "caribou" was derived from the Micmac "xalibu" which means "the power." The term for caribou varies in the Sahtu from community to community. In Deline, the term is “ɂékwę́” and the people in Fort Good Hope say “ɂedǝ.” European explorers naturally called these animals reindeer, or simply deer, the terms used for this species in the Old World.

Ɂékwę́ Deyúe Ɂehdaralǝ

when caribou changes its clothes

Story told by Deline elder William Sewi

Ɂékwę́ (caribou) migrates to the barrengrounds, even though it doesn't have navigating tools. It still travels straight. It migrates to change its clothing, just the way a man would change his clothing when it wears out.

There is a kind of ɂékwę́ known in the Deline dialect as bele yah (eseloea in the K'ahsho Got'ine dialect). It looks like a two year old ɂékwę́. And it is said that it is the boss of all ɂékwę́.

Bele yah scouts up ahead of the herd. When it finds a good feeding ground, it goes back and rounds up the herd, and leads them to the area. Yes, it is the boss of all ɂékwę́.

It is amazing how straight it travels. They say it is as intelligent as humans.

Along the migration route to the barrengrounds, there is a hill called Radú Dahk'ale (white outcrop). It has been said that this is where Ɂékwę́ changes its footwear.

The same as we humans do when our moccasins wear out, so it's been said that Ɂékwę́ changes its footwear on this hill. It is said that Ɂékwę́ sang a song on this hill. This song was not passed on.

From that hill, Ɂékwę́ continues along on the barrengrounds. It goes a long way, all the way to its calving grounds.

It has been said that Ɂékwę́ rears its young as people do. When it licks its young one, it is actually changing its diaper.

There is an inscription in the skull of Ɂékwę́. It is written in a strange language. They say that one day in the future, someone will be able to interpret the inscription.

Whenever it rains, Ɂékwę́ feeds good, and that's how Ékwę́ gets fat. Like if we ate dry food, for example, we wouldn't like it! But if the food is boiled, it is very good for us.

Long ago when it rained, people used to exclaim, "Haaay, it's raining! That's great, Ɂékwę́ is going to be fat!"

Caribou poems by Carla Kenny, Grade 5, Deline - 2001

I

caribou, caribou

come to my land

caribou, caribou

we love you

caribou, caribou

we will catch you

caribou, caribou

we will cut you up

caribou, caribou

we will eat you.

II

we love caribou,

we will hunt them,

we will eat them,

you will be in our stomach,

you will die.

caribou are good to eat

they are healthy for our heart.

III

caribou soup, caribou soup

you are so good

caribou soup, caribou soup

you are so yummy

Caribou Parts Classified By Food Groups

Milk and Milk Products

soft ends of bones

stomach contents

intestines

Meat and Alternatives

meat, heart, liver

kidneys, brain, blood

Bread and Cereals

heart, liver, kidneys

bone marrow

intestines

web covering stomach

Fruits and Vegetables

stomach contents

eyes, liver

Caribou on the Move

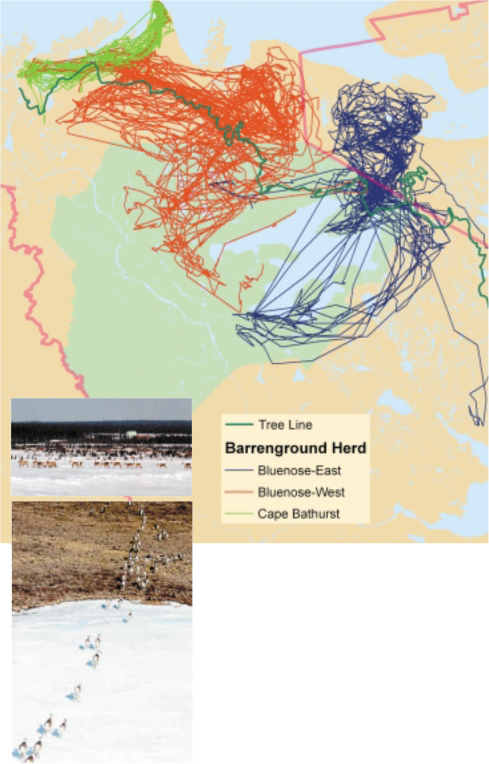

This map of caribou migration patterns over the past five years is the product of a satellite collaring program initiated by RWED in 1996. The project was a model of cooperative management, with the support and involvement of aboriginal representatives. It was co-funded by the Inuvialuit Land Claim Implementation funds, Gwich'in Renewable Resource Board, Sahtu Renewable Resources Board, GNWT, and the Nunavut Wildlife Management Board. The project leaders were Resource Wildlife and Economic Develelopment biologists John Nagy and Alasdair Veitch.

By mapping migration patterns and studying the genetics of samples from caribou antlers that have been dropped by cows on calving grounds, scientists have confirmed the existence of three separate herds in the northwest mainland of the Northwest Territories and Nunavut. These are known in English as the Bluenose-East, Bluenose-West, and Cape Bathurst herds. This map shows the two herds that migrate through the Sahtu Region.

Having sorted out the existence of the three herds, it now becomes possible to get population estimates and other information specific to each herd. Along with traditional knowledge about caribou, this information will assist in monitoring the health of the herds over the long term.

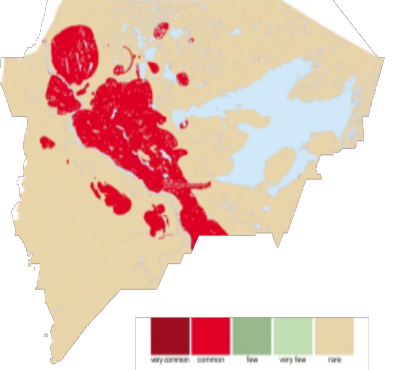

There are two ecotypes of woodland caribou in the Sahtu Region, which are differentiated by habitat use. Boreal woodland caribou are non-migratory and remain in forested regions outside the Mackenzie Mountains year-round. Mountain woodland caribou migrate between forested and alpine habitats throughout the Mackenzie Mountains and parts of the Mackenzie Valley.

Above map: coloured lines shows the yearly movement of individual mountain woodland caribou through the Mackenzie Mountains

Data obtained by RWED from caribou fitted with satellite collars.

Boreal woodland caribou

Woodland Caribou

Woodland caribou that live in the boreal forests of Canada (boreal caribou) are a type of caribou that is considered to be different from the large, migratory barrenground herds, and from the woodland caribou that live in the Mackenzie Mountains, which are known as "mountain caribou." However, genetically both boreal and mountain caribou are in the same subspecies. They just have a different "lifestyle" whereby the boreal caribou live in small, rather isolated groups and prefer areas of old growth conifer forest.

One thing that we know about boreal caribou is that they are sensitive to activities associated with oil and gas exploration and extraction, particularly the cutting of seismic lines through the forests in which the caribou live.

Extensive research in northeastern Alberta done by Alberta's Boreal Caribou Research Program (BCRP) have found that wolves can travel much faster through the forest along seismic lines than through the bush, especially during the summer. This increases their efficiency at finding and killing radiocollared caribou.

As a result of this increased risk of predation, the radio-collared caribou were more likely to be found in habitats that were at least 250 meters from seismic lines.The areas within 250 meters of seismic lines can therefore be considered to be areas of habitat loss for caribou, just as if those patches of habitat had been cut, burned by forest fire, or otherwise altered.

Biologists are examining the density of seismic lines across the Sahtu to determine the current oil and gas "footprint" in our region in light of what we know about such activity and its impact on caribou in Alberta. This information will be shared with the communities, with co-management boards, and with organizations with responsibility for environmental impact assessment.

Mountain woodland caribou

Caribou and Nutrition

Adapted from "Nutrition," by Jill Christensen, in People and Caribou in the Northwest Territories, Ed Hall, Editor (1989).

Caribou has long been a staple food for the Dene people of the Sahtu. Now, every community has at least one food store.

This is a mixed blessing. On the one hand it means that starvation, which was once common, is no longer a threat. On the other hand, stores are a source of many foods whose nutritional value is considerably lower and less complete than traditional country food. To this day, caribou remains a key source of nutrition for many people.

Caribou can provide nutrients that would require eating a wide variety of foods in a modern diet - not only meat, but also milk, bread, fruits and vegetables. The only essential nutrient that is not found in caribou is vitamin D. Traditionally, people had to use other food such as fish liver oil to get this.

Caribou will provide such a complete source of nutrition only if all the parts are eaten. Caribou liver is rich in vitamin C, but caribou muscle is not. If the liver isn't eaten, it is necessary to get vitamin C from another food source.

Caribou is leaner than most store-bought meats. Caribou fat is also better for you, since it is more "unsaturated." This means that those who eat it are in less danger of getting heart disease.

Eating country foods such as caribou can also prevent other diseases, such as diabetes which as become distressingly common in communities more dependent on store-bought food.

[ Sahtu Atlas Table of Contents ]

[ Next Section ]

Phone: 867-374-4040

Phone: 867-374-4040 Email:

Email: