Tulı́t'a

Tulı́t’a

There is a thing I would like to say about the oil in Łegǫ́́łı̨ (Norman Wells). What was the name of the man who found that oil? It was our own father, Francis Nineye. When he found the oil, he took a sample of it, put it in a lard pail and brought it out into Tulit'a (Fort Norman). That same summer, he had an accident and died.

Now the white people turn around and claim they found the oil. My dad was the first guy to find that oil...He was staying right where Łegǫ́́łı̨ is now, and the Dene had about five or six log shacks. They were trapping and hunting there for a living. He took the sample of that oil in a lard kettle and brought it into Tulit'a. He gave it to Gene Gaudet, the Hudson's Bay Manager and he sent it out on the boat, it had to be a boat, there was no planes then. We never heard of that oil again and we never got the lard kettle back. We never could do anything about it again. There is no record.

John Blondin, from Dene Cultural Institute, Dehcho: “Mom, we’ve been discovered!” Yellowknife: Dene Cultural Institute, 1989. 40.

Tulita is named for its location where the Sahtu Deh/Great Bear River flows into Deh Cho/Mackenzie River, “where the waters meet.” Great Bear River is the Dene travel route to Great Bear Lake, where people of the Sahtu Region travel to hunt for caribou, and rarely, muskoxen. Since ancient times, people would camp at Tulita across from the huge limestone outcropping known as Kweteniɂaá /Bear Rock, an important site in Dene lore. The Northwest Company established Fort Norman as a fur trading post at this crossroad in 1810 to encourage trade with peoples south of Fort Good Hope and with the Sahtúot’ine of Great Bear Lake. When the Hudson’s Bay Company took over the post, it was relocated several times, but by 1851 it returned to the original site.

The Dene people of Tulita are known for having revived the traditional skill of making moose skin boats. This was the first such boat to be built in decades. It is thought that the boats came into use during the fur trade. Their construction combines the ancient design of the smaller Dene birch and spruce bark canoes, and the shallow, broad and long York boats developed by fur traders in the 19th century to navigate the inland rivers of Canada with large loads. A second moose skin boat was constructed for the documentary film The Last Moose Skin Boat, and the boat remains preserved at the Prince of Wales Heritage Centre.

Situated within an oil-rich district, the people of Tulita have had to become adept at negotiating with petroleum interests, and many young community members have found jobs in the industry. At the same time, the community is taking measures to protect traditional heritage sites.

Bear Rock and winter road Watching the Mackenzie River, Tulita © R. Kershaw

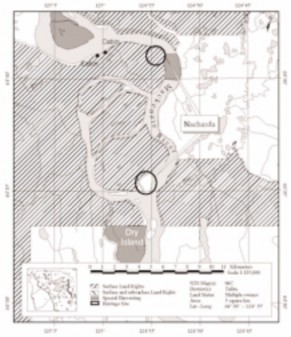

Nachaɂda / Old Fort Point

Fort Norman was constructed in 1810 at the confluence of the Mackenzie and Great Bear Rivers. In 1844 it was moved about 48 km upstream to a site a few miles below the Keele River, called ‘Old Fort Point’, near the site of the old North West Co. Fort Castor. In 1851 it was moved back to its present site.

Archaeological investigations at Old Fort Point in the summer of 1973 recorded the presence of two storage cellar depressions and the remains of two stone chimney piles. The archaeologists noted that the site had undergone considerable erosion. Artifacts recovered from the site include a kaolin pipe stem, a small strip of copper, and pieces of chinking clay, as well as several fragments of moose, caribou, and beaver bones. Fort Castor, built in 1804, was never located during the archaeological survey. On the site map (below) we have marked two locations; one at Old Fort Point (the site of old Fort Norman) and a second site to the south. Local tradition indicates that this might be the remains of another post and may be Fort Castor. From Rakekée Gok’é Godi: Places We Take Care Of.

Tuwí Tué / Mahony Lake Massacre Site

The story is still recounted in the oral tradition of Tulita, and an excellent description of the event and trial proceedings can be found in Foster (1989). Foster (1989) remarks that the case is important to Canadian social and judicial history because “it is the only offence ever tried by a Canadian court during the HBC’s licenced monopoly over the Indian Territories, [and] stands as a little known example of how imperial law was enforced in the fur trade.

In December of 1835 three employees of the Hudson’s Bay Company Post at Fort Norman were sent to collect a cache of fish at Mahony Lake. Encamped near the lake was a Dene family who, according to oral tradition, were employed to provide meat and fish for the HBC post. Partly as a result of earlier problems between one of these men and a young married Dene woman, a terrible fight ensued, and the three Hudson’s Bay employees murdered eleven men, women, and children. One of the men was sent to London, England for trail, and was later transported to Canada. Another was tried for murder in Lower Canada (largely as a result of testimony given by one of his accomplices) and was sentenced to hang, which was later commuted to transportation to Australia. While awaiting a transportation, he was jailed in a prison hulk in England for several years, where he died. The last man was imprisoned for a short period while awaiting trial but was eventually set free after giving testimony against his accomplice.

Sahtu Heritage Places and Sites Joint Working Group, Rakekée Gok’é Godi: Places We Take Care Of.

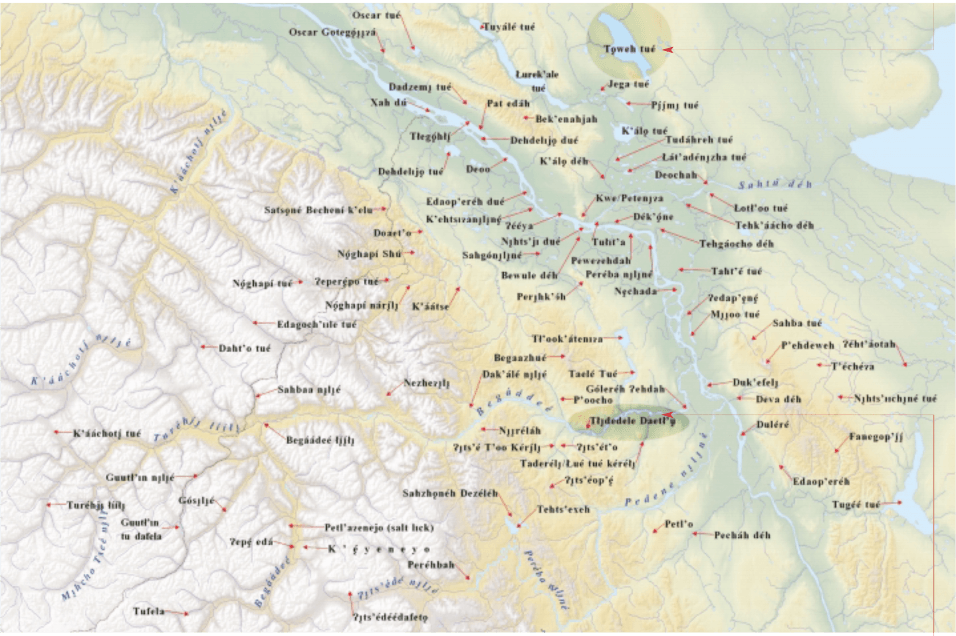

Tulita Traditional Place Names project map

Tłı̨ Dehdele Dı̨dlǫ/ Red Dog Mountain

The site is a large mountain located on the Keele River, considered a sacred site by the Mountain Dene. A Tulita elder relates the historical and cultural importance of the site:

Keele River

Long ago, when people went by Red Dog Mountain, they never passed the mountain on the river. They used to get out of the river and portage through the mountains and put in again below Red Dog Mountain. ... When they got to Red Dog Mountain, the men portaged because the Red Dog would take and eat them. That is why they always portaged. One time, when they were all gathered getting ready to portage when a man who had medicine and was a really good hunter said, "Give me all of your possessions." He took mitts, moccasins, weapons, and food. He gathered all of their possessions together and put them in his canoe. He then turned to the people and said I am going to go down the river past the Red Dog Mountain. He wanted to know why the mountain took people. As he started down the river a whirlpool opened before him. He started throwing all the goods into the water to pay. After he threw all the goods into the water the eddy subsided and let him go down the river. Up to that time they did not know what was living at Red Dog Mountain. When he went through the mountain he saw the Red Dog for the first time. He told the people that every time they pass Red Dog Mountain they must show respect. You must pay the Red Dog with something. So people started leaving matches and shot when they passed by on the river as an offering. One time long ago when people were passing by Red Dog Mountain, the spring that pours from the face of the mountain into the river whistled and spurted water like steam. They did not know what it meant at the time, but that year the first tuberculosis epidemic occurred. The elders knew that it was a sign that something was wrong. A few years later it whistled ... and ... spit out water again before sickness again struck the people.

Sahtu Heritage Places and Sites Joint Working Group, Rakekée Gok’é Godi: Places We Take Care Of.

[ Sahtu Atlas Table of Contents ]

[ Next Section ]

Phone: 867-374-4040

Phone: 867-374-4040 Email:

Email: